The Dave Heerensperger / Pay ‘n Pak Saga

U-1 Pay N Pak

By Fred Farley – APBA Unlimited Historian

Unlimited hydroplane racing, at its best, represents the ultimate in “no holds barred” experimental boat racing. The door is always open to new ideas. Anything goes.

Dave Heerensperger, owner of the PAY ‘n PAK and MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC boats, stands tall as one of the sport’s all-time great innovators. He was never afraid to try something new.

Not all of his experiments with hull design and power sources met with success. His 1969 outrigger PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK failed to make the competitive grade. And his 1970 attempt at automotive power proved disappointing.

But Heerensperger’s 1973 success with the “Winged Wonder” PAY ‘n PAK is legendary. “Dynamite Dave” likewise deserves praise as the first Unlimited owner to win a race with turbine power in 1982.

Between 1968 and 1982, Heerensperger’s team won 25 races, including two Gold Cups, and three National High Point Championships. In 1973, the “Winged Wonder” set a world lap speed record of 126.760 on a 3-mile course on Seattle’s Lake Washington with Mickey Remund driving.

The Heerensperger dynasty also had its dark side. Two drivers were fatally injured in hydroplane accidents–Warner Gardner in 1968 with the second MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC and Tommy Fults in 1970 with PAY ‘n PAK’S ‘LIL BUZZARD.

Dave sponsored his own boats. In 1969, he merged his Spokane, Washington-based Eagle Electric and Plumbing firm with the Pay ‘n Pak Corporation. He went on to found Eagle Hardware and Garden, Inc., before selling it to Lowe’s in 1999.

Heerensperger entered boat racing in 1963. He read in THE SPOKANE CHRONICLE that the MISS SPOKANE hydroplane team needed a sponsor and was looking for someone who would invest $5,000. Renamed MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC, the boat finished third in the 1963 Harrah’s Tahoe Regatta with Rex Manchester driving and fourth in the 1964 Seattle Seafair Regatta with Norm Evans.

Dave became his own owner in 1967 when he bought the veteran $ BILL from Bill Schuyler. $ BILL was a 1962 Les Staudacher hull. It had never won a race and, as a contender, was lightly regarded. But while Schuyler regarded racing as strictly a hobby, Heerensperger ran his race team in the same aggressive way that he ran his business.

Nicknamed the “Screaming Eagle,” the second MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC caught the racing world by surprise in 1968. With Warner Gardner as driver and Jack Cochrane as crew chief, the Heerensperger team trampled the opposition en route to victories in the Dixie Cup at Guntersville, Alabama, the Atomic Cup at the Tri-Cities, Washington, and the President’s Cup at Washington, D.C.

Moreover, MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC posted a 3-mile lap of 120.267 in qualification at Seattle. This duplicated exactly the then-current world lap speed record set by Bill Stead in MAVERICK on the same race course ten years earlier.

Heading into the 1968 Gold Cup, MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC and the Billy Schumacher-chauffeured MISS BARDAHL had both won three races that season.

The fans looked forward to a classic confrontation between Schumacher and Gardner on the historic Detroit River. But the 1968 Gold Cup emerged as one of the more tragic chapters in Thunderboat history.

MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC, which had finally come alive after so many years of mediocrity as $ BILL, disintegrated on the backstretch of the third lap of the Final Heat. She was leading MISS BARDAHL and challenging Bill Sterett in MISS BUDWEISER. Then, the EAGLE became airborne and cartwheeled itself to pieces in the vicinity of the Detroit Yacht Club. Warner Gardner never regained consciousness.

Solemn but undaunted after the loss of his driver and friend, Heerensperger went ahead with plans for the 1969 season. He chose as Gardner’s replacement the 1968 Unlimited Rookie of the Year, Tommy “Tucker” Fults. “Tucker” had won the San Diego Cup with Jim Ranger’s MY GYPSY.

Dave’s new flagship was the outrigger PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK, a Staudacher creation. It had originally been intended as a straightaway runner but was altered to run on a closed course. Unfortunately, the craft proved unsatisfactory in either format and was quickly retired.

The outrigger hull made a bid for the world mile straightaway record of 200 miles per hour but could only reach 162 in trials on Guntersville Lake. Its fastest heat was only 94 miles per hour on a 3-mile course at Seattle.

Heerensperger unveiled his second Unlimited Class experiment in 1970. He achieved better results than the first but still fell short of expectation. This PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK used a pair of 426 cubic inch supercharged Chrysler hemis and featured a pickle-fork bow.

Designed and built by Ron Jones, Sr., the boat featured a cabover configuration with the driver sitting ahead of the engine well, a concept that was not widely accepted at the time. The design was an evolution of Ron’s 225 Cubic Inch Class TIGER TOO of 1961, the Unlimited Class MISS BARDAHL of 1966, and the 7-Litre Class RECORD-7 of 1969.

The Chrysler-powered PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK showed some good bursts of speed at times but wasn’t fast enough to be truly competitive with the aircraft engine-powered boats.

1970 Pay N Pak

According to Jones, “The boat was a little too heavy for two Chryslers. We didn’t have the propeller technology that we have today. I wish that I had had the propeller and gear ratio combinations in 1970 that we are able to enjoy today. We might have been a great deal more successful.”

At the last race of 1970 in San Diego, Heerensperger’s team again experienced the ultimate downer. Tommy Fults was killed in a freak accident during testing with PAY ‘n PAK’S ‘LIL BUZZARD, a conventional Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered entry.

Fults died of a broken neck when he encountered a wake and was flipped out of the boat. He had been wearing a car racing helmet, which was permitted–but not recommended–for boat racing.

Built by Les Staudacher, the BUZZARD had won the 1970 Tri-Cities Atomic Cup and had the distinction of turning the fastest heat of the 1970 season at Seattle (108.433) with Fults at the wheel.

PAY ‘n PAK’S ‘LIL BUZZARD never raced again after 1970. It sat in storage for several years and eventually became an ATLAS VAN LINES display hull.

For 1971, Heerensperger hired Billy Schumacher as driver and promoted Jim Lucero to crew chief. During the off-season of 1970-71, Lucero changed the PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK from a cabover to a conventional configuration with the cockpit situated behind–rather than in front of–the engine well. Lucero replaced the twin Chryslers with a single Rolls-Royce Merlin. The boat was wider, flatter, and less box-shaped than most Unlimiteds of that era.

The Merlin-powered PAK performed unevenly in the first half of 1971. But there were those who believed that if PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK ever had the “bugs” ironed out of her, she would revolutionize the sport, and render obsolete all of the top contenders of the previous twenty years. This ultimately proved to be the case.

Schumacher powered the PAK to victory in the last three races of the season at Seattle, Eugene, and Dallas and set a world lap speed record of 121.076 in qualification at Seattle. The boat that had disappointed so badly the year before as an automotive-powered cabover, now ruled the Unlimited roost.

Dave Heerensperger now had seven race wins as an owner. His team’s recent difficulties seemed a thing of the past. PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK seemed poised for a National Championship bid in 1972. But things didn’t work out that way.

Joe Schoenith’s ATLAS VAN LINES team, after an uneven 1971, had its act together in 1972 and driver Bill Muncey was really on a roll. Schumacher and PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK ran a frustrating second to Muncey at each of the first three races of the season at Miami, Owensboro, and Detroit.

Schumacher and Lucero were at odds on how to set up the boat. After being decisively defeated in every race by ATLAS VAN LINES, Schumacher left the PAY ‘n PAK team the weekend after Detroit at Madison, Indiana.

Where Schumacher and Lucero were concerned, it was a case of an irresistible force against an unmovable object.

On a race team, there can be only one leader. Everyone must pull in the same direction. A team must be unified or there is chaos.

Former champion Bill Sterett, Sr., came out of retirement to pilot the PAK at Madison. He failed to start in Heat One but ran the fastest heat of the race in Heat Two. (Heat Three was cancelled due to inclement weather conditions.)

PayNPak in DC – Bill Sterett Jr

Billy Sterett, Jr., drove the last three races of the 1972 season. He scored a sensational victory over ATLAS VAN LINES in the President’s Cup and, in so doing, handed Bill Muncey his only defeat of the year. After a frustrating series of early-season setbacks, PRIDE OF PAY n PAK appeared to be back on track and highly favored for the Atomic Cup and Seafair Trophy races.

Sterett, Jr., and the PAK were indeed an awesome sight to behold during qualification at the Pacific Northwest regattas. They qualified fastest at both events. And, at Seattle, the team achieved owner Heerensperger’s goal of a lap of 125 miles per hour with a clocking of 125.878 on a 3-mile course.

Race day was a different story. At the Tri-Cities, after winning the first two heats, the Rolls engine conked out at the start of the finale. At Seattle, PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK again experienced mechanical difficulty and failed to complete even a single lap. In Heerensperger’s words, “When we’re hot, we’re hot. Today, we’re not.”

At this point, Dave decided to accept an offer from his good friend Bernie Little, the MISS BUDWEISER owner, and sold his record-holder to the Anheuser-Busch team. The day after the Seafair race, Heerensperger met with designer Ron Jones to plan a new boat for 1973, the “Winged Wonder,” which would prove to be one of the most significant boats in hydroplane history.

After 1972, the words PRIDE OF were dropped from the Heerensperger team’s official name. For the rest of Dave’s racing career, all of his boats would be known as simply PAY ‘n PAK. The 1973 “Winged Wonder” was the first hydroplane of any shape or size to be built of aluminum honeycomb, rather than marine plywood.

According to Jones, “I had originally thought that I would use a honeycomb bottom. But after talking with the people from the Hexcel Company, I was very impressed and decided to use it everywhere in the boat that I possibly could for a weight saving of about a thousand pounds.”

Pay N Pak

In planning the new PAY ‘n PAK, Jones wanted very much to build a cabover. But Heerensperger insisted on a rear-cockpit hull and won out. Ron nevertheless utilized many of the cabover hull characteristics while still seating the driver behind the engine.

“But I did insist on the use of a horizontal stabilizer. Heerensperger agreed because it would give him a lot of publicity. And it did. Perhaps, by today’s standards, the stabilizer was not everything it could have been. It was, however, a good running start on the widespread use of the concept. And in all fairness to Jim Lucero, he certainly added to the boat’s ultimate performance by preparing excellent engines, good gearbox/propeller combinations, and probably some fine-tuning on the sponsons.”

The “Winged Wonder” PAY ‘n PAK set a Gold Cup qualification record for two laps in 1973 at 124.309 on the 2.5-mile Columbia River course. This translated to approximately 129 miles per hour on a 3-mile course.

The 1973 season was the first in which the majority of races were won by Ron Jones-designed hulls. The new PAY ‘n PAK and its predecessor (now the MISS BUDWEISER) won four races apiece on the nine-race circuit.

At Seattle in 1973, the PAY ‘n PAK with Mickey Remund and the MISS BUDWEISER with Dean Chenoweth became the first two teams to average over 120 miles per hour in a heat of competition. And they did this in a driving rain! MISS BUDWEISER averaged 122.504 for the 15 miles; PAY ‘n PAK did 120.697. A local newspaper labeled the PAK and the BUD as “the champion fogcutters of the world.”

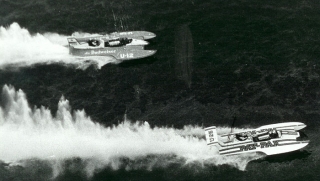

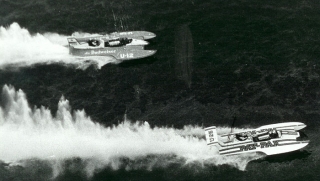

Pay N Pak and Bud

Although not significantly faster on the straightaway than the traditional post-1950 Ted Jones-style hulls, the Ron Jones-designed PAY ‘n PAK and MISS BUDWEISER could out-corner anything on the water. Both boats were helped considerably by the inclusion of an outboard skid fin. The skid fins helped greatly in holding the boats in their lanes through the turns.

In spite of being three years older and a thousand pounds heavier than PAY ‘n PAK, MISS BUDWEISER was able to achieve parity with the PAK. This was due to driver Chenoweth consistently securing the inside lane in heat confrontations between the two entries. PAY ‘n PAK ended up with the first of the team’s three consecutive National High Point Championships in 1973. The only major disappointment was at the Tri-Cities Gold Cup.

Pilot Remund appeared to have things well in hand. He won his three preliminary heats and had a clear lead in the finale. Then, on lap-two, the PAK lost a blade on its propeller. The boat bounced crazily a couple of times and settled to a stop. MISS BUDWEISER went on to claim the victory. This was a most unfortunate turn of events for Remund who had posted a Gold Cup competition lap record of 119.691 miles per hour on the first lap of the Final Heat on a 2.5-mile course.

The 1973, ‘74, and ‘75 seasons are fondly remembered as “The PAK/BUD Era” of Unlimited racing. The many side-by-side battles by those two awesome machines are unforgettable. Their owners, too, were larger than life. Dave Heerensperger and Bernie Little gave no quarter and asked for none. To them, second-place was an insult.

And yet, as competitive as their teams were out on the race course, the two men were close personal friends. In 1974, when Dave married his wife Jill, Bernie was Best Man at their wedding.

PAY ‘n PAK and MISS BUDWEISER picked up in 1974 where they had left off in 1973–but this time with different drivers. George Henley now occupied the PAK’s cockpit; Howie Benns handled the BUD. (Chenoweth did briefly return to the BUDWEISER team in late season after Benns suffered a broken leg in a motorcycle accident.) The PAK won seven races and the BUD won four.

The most memorable PAK/BUD match-up of 1974 would have to be the 1974 Seattle Gold Cup at Sand Point. Delays, controversy, and rough water marred the running of the race but PAY ‘n PAK finally prevailed and Dave Heerensperger was able to take his first Gold Cup home–but only after a titanic struggle.

Henley and Benns battled head to head all day long in some of the finest racing ever witnessed in the Unlimited Class. PAY ‘n PAK won all four heats with MISS BUDWEISER always within striking distance. The BUD had the lead in Heat 1-C but spewed oil briefly and was overtaken by PAY ‘n PAK. Heat 1-C was the fastest of the day with Henley averaging 112.056 miles per hour and Benns 109.845. No one else averaged over 100 all day long because of the rough water.

George Henley made it two Gold Cups in a row for Heerensperger at the Tri-Cities in 1975. The “Winged Wonder” won her three preliminary heats and then cruised to an easy third in the finale behind Tom D’Eath in MISS U.S. and Milner Irvin in LINCOLN THRIFT.

In the space of three years, the low-profile/wide-afterplane Ron Jones-style hull had become the dominant design in Unlimited racing. (Ted Jones, Ron’s father, had likewise revolutionized the sport in the 1950s, starting with SLO-MO-SHUN IV.)

The PAY ‘n PAK’s road to victory in 1975 was not an easy one. After a stellar 1974 campaign, George Henley retired as driver and Jim Lucero rebuilt the boat. In spring testing, PAY ‘n PAK was definitely faster on the straightaways but was skittish in the turns.

New driver Jim McCormick (on the rebound from a serious injury accident in 1974 with RED MAN) had great difficulty in cornering the PAK and was the subject of considerable criticism. McCormick retired from racing after a third-place finish in the 1975 President’s Cup.

Henley was coaxed out of retirement and returned to the PAY ‘n PAK cockpit at the third race of the season in Owensboro, Kentucky. Lo and behold, George had the same problem with the PAK that Jim had experienced. On the first lap of the first heat at Owensboro, PAY ‘n PAK swapped ends, caved in a sponson, and had to be withdrawn. All of a sudden, the Jim McCormick detractors became the George Henley apologists.

PAY ‘n PAK continued to perform badly at the next race in Detroit. Finally, Lucero restored the boat to its 1974 configuration. Only then was the PAK its old competitive self again. Henley and PAY ‘n PAK picked up where they had left off the year before with victories at Madison, Indiana, and Dayton, Ohio. After winning at the Tri-Cities, the team went on to take first-place in Seattle and San Diego en route to a third consecutive National High Point Championship.

Earlier in the season, the Billy Schumacher-chauffeured WEISFIELD’S had seemed a shoo-in for the national title. They had scored convincing victories at Miami and Owensboro and finished second at Washington, D.C. But once PAY ‘n PAK was back on track, the chances for a WEISFIELD’S championship promptly vanished.

The MISS BUDWEISER team had an uneven 1975 campaign. They won two races (at Washington, D.C., and Phoenix, Arizona) with Mickey Remund driving, but in general lacked the consistency that marked the 1973 and 1974 seasons.

After two dozen race victories and having re-written the speed record book from coast to coast, Heerensperger decided to rest on his laurels for a while. “We’ve accomplished everything we set out to do and more.”

In January of 1976, he accepted an offer from Bill Muncey’s ATLAS VAN LINES team and sold the entire PAY ‘n PAK equipment inventory for a figure in the six digits. Inactive as an owner between 1976 and 1979, Dave nevertheless stayed close to the sport that he loved. He sponsored the boat that he had most recently owned–the ”Winged Wonder”–at two 1977 races. He also sponsored the 225 Class WHITE LIGHTNING, owned and driven by Steve Reynolds, as PAY ‘n PAK.

Always on the lookout for new ideas, Heerensperger began serious speculation into the possibility of turbine power in an Unlimited hydroplane. Between 1980 and 1982, he campaigned just such a craft. Jim Lucero designed the hull. The highly regarded Dixon Smith, who happened to be Heerensperger’s personal pilot, developed the turbine engine concept.

Turbine Pay N Pak

The turbine PAY ‘n PAK was the first turbine-powered Unlimited since Pam Clapp’s U-95 in 1974. Unlike the U-95, which used a pair of T-53 engines, PAY ‘n PAK used a single Lycoming T-55 power plant, thereby establishing a precedent for turbine-powered Unlimiteds of the future.

The new boat’s first appearance (at the 1980 Tri-Cities Columbia Cup) proved disastrous. Rookie driver John Walters flipped the boat in trials on the Columbia River and delayed the team’s competition debut until the following year. Walters steered the turbine PAY ‘n PAK to some high finishes in 1981, which included a second-place performance in the Champion Spark Plug Regatta at Miami and a second in the Gold Cup at Seattle.

During the Final Heat of the Gold Cup, Walters gave the winner Dean Chenoweth in the MISS BUDWEISER everything he could handle. MISS BUDWEISER averaged 123.814 to PAY ‘n PAK’s 122.223.

The PAK finally achieved victory in 1982 at “Thunder In The Park” at Romulus, New York. In the long history of Unlimited hydroplane competition, this was a famous first–the first victory by a non-internal combustion-powered craft.

The turbine was the power source of today. In contrast, the Allison, the Rolls-Royce Merlin, and the Rolls-Royce Griffon had ceased production almost forty years earlier.

Her triumph at Romulus not withstanding, PAY ‘n PAK did not have much of an opportunity to build upon this accomplishment. The boat damaged its right sponson in Heat 1-B at the Gold Cup in Detroit and had to withdraw. A few weeks later, Walters was badly hurt and the boat was extensively damaged in an accident at the Emerald Cup on Lake Washington.

Pay N Pak flips in Seattle

Moments after the start of Heat 1-B at Seattle, George Johnson, driving EXECUTONE, experienced rudder failure. The boat dug in its right sponson and veered to the left and crashed into the right side of Tom D’Eath and THE SQUIRE SHOP. The impact sent EXECUTONE back to the right and into the path of a late-starting PAY ‘n PAK. The PAK ran right over EXECUTONE and flipped. EXECUTONE sank almost immediately. THE SQUIRE SHOP managed to limp back to the pits under its own power, while PAY ‘n PAK had to be towed back to the dock.

Johnson and D’Eath were unhurt. But Walters was critically injured with several broken bones and a collapsed lung. John recovered and continued in the sport for many years as a shore mechanic. But he never drove in competition again.

After the accident to his boat and the injury to his driver, Dave Heerensperger announced his retirement from Unlimited racing and sold his team to Steve Woomer. Heerensperger had first joined the sport in 1963 as the sponsor of MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC. “Dynamite Dave” had left before. But this time it was for good.

As in the case of the U-95 eight years earlier, the PAY ‘n PAK team’s innovative turbine concept passed into history, but not for long. In the not too distant future, the Lycoming turbine engine would return and revolutionize the sport.

Thanks to Bill Osborne & The Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum for photos

The Dave Heerensperger / Pay ‘n Pak Saga

U-1 Pay N Pak

By Fred Farley – APBA Unlimited Historian

Unlimited hydroplane racing, at its best, represents the ultimate in “no holds barred” experimental boat racing. The door is always open to new ideas. Anything goes.

Dave Heerensperger, owner of the PAY ‘n PAK and MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC boats, stands tall as one of the sport’s all-time great innovators. He was never afraid to try something new.

Not all of his experiments with hull design and power sources met with success. His 1969 outrigger PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK failed to make the competitive grade. And his 1970 attempt at automotive power proved disappointing.

But Heerensperger’s 1973 success with the “Winged Wonder” PAY ‘n PAK is legendary. “Dynamite Dave” likewise deserves praise as the first Unlimited owner to win a race with turbine power in 1982.

Between 1968 and 1982, Heerensperger’s team won 25 races, including two Gold Cups, and three National High Point Championships. In 1973, the “Winged Wonder” set a world lap speed record of 126.760 on a 3-mile course on Seattle’s Lake Washington with Mickey Remund driving.

The Heerensperger dynasty also had its dark side. Two drivers were fatally injured in hydroplane accidents–Warner Gardner in 1968 with the second MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC and Tommy Fults in 1970 with PAY ‘n PAK’S ‘LIL BUZZARD.

Dave sponsored his own boats. In 1969, he merged his Spokane, Washington-based Eagle Electric and Plumbing firm with the Pay ‘n Pak Corporation. He went on to found Eagle Hardware and Garden, Inc., before selling it to Lowe’s in 1999.

Heerensperger entered boat racing in 1963. He read in THE SPOKANE CHRONICLE that the MISS SPOKANE hydroplane team needed a sponsor and was looking for someone who would invest $5,000. Renamed MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC, the boat finished third in the 1963 Harrah’s Tahoe Regatta with Rex Manchester driving and fourth in the 1964 Seattle Seafair Regatta with Norm Evans.

Dave became his own owner in 1967 when he bought the veteran $ BILL from Bill Schuyler. $ BILL was a 1962 Les Staudacher hull. It had never won a race and, as a contender, was lightly regarded. But while Schuyler regarded racing as strictly a hobby, Heerensperger ran his race team in the same aggressive way that he ran his business.

Nicknamed the “Screaming Eagle,” the second MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC caught the racing world by surprise in 1968. With Warner Gardner as driver and Jack Cochrane as crew chief, the Heerensperger team trampled the opposition en route to victories in the Dixie Cup at Guntersville, Alabama, the Atomic Cup at the Tri-Cities, Washington, and the President’s Cup at Washington, D.C.

Moreover, MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC posted a 3-mile lap of 120.267 in qualification at Seattle. This duplicated exactly the then-current world lap speed record set by Bill Stead in MAVERICK on the same race course ten years earlier.

Heading into the 1968 Gold Cup, MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC and the Billy Schumacher-chauffeured MISS BARDAHL had both won three races that season.

The fans looked forward to a classic confrontation between Schumacher and Gardner on the historic Detroit River. But the 1968 Gold Cup emerged as one of the more tragic chapters in Thunderboat history.

MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC, which had finally come alive after so many years of mediocrity as $ BILL, disintegrated on the backstretch of the third lap of the Final Heat. She was leading MISS BARDAHL and challenging Bill Sterett in MISS BUDWEISER. Then, the EAGLE became airborne and cartwheeled itself to pieces in the vicinity of the Detroit Yacht Club. Warner Gardner never regained consciousness.

Solemn but undaunted after the loss of his driver and friend, Heerensperger went ahead with plans for the 1969 season. He chose as Gardner’s replacement the 1968 Unlimited Rookie of the Year, Tommy “Tucker” Fults. “Tucker” had won the San Diego Cup with Jim Ranger’s MY GYPSY.

Dave’s new flagship was the outrigger PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK, a Staudacher creation. It had originally been intended as a straightaway runner but was altered to run on a closed course. Unfortunately, the craft proved unsatisfactory in either format and was quickly retired.

The outrigger hull made a bid for the world mile straightaway record of 200 miles per hour but could only reach 162 in trials on Guntersville Lake. Its fastest heat was only 94 miles per hour on a 3-mile course at Seattle.

Heerensperger unveiled his second Unlimited Class experiment in 1970. He achieved better results than the first but still fell short of expectation. This PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK used a pair of 426 cubic inch supercharged Chrysler hemis and featured a pickle-fork bow.

Designed and built by Ron Jones, Sr., the boat featured a cabover configuration with the driver sitting ahead of the engine well, a concept that was not widely accepted at the time. The design was an evolution of Ron’s 225 Cubic Inch Class TIGER TOO of 1961, the Unlimited Class MISS BARDAHL of 1966, and the 7-Litre Class RECORD-7 of 1969.

The Chrysler-powered PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK showed some good bursts of speed at times but wasn’t fast enough to be truly competitive with the aircraft engine-powered boats.

1970 Pay N Pak

According to Jones, “The boat was a little too heavy for two Chryslers. We didn’t have the propeller technology that we have today. I wish that I had had the propeller and gear ratio combinations in 1970 that we are able to enjoy today. We might have been a great deal more successful.”

At the last race of 1970 in San Diego, Heerensperger’s team again experienced the ultimate downer. Tommy Fults was killed in a freak accident during testing with PAY ‘n PAK’S ‘LIL BUZZARD, a conventional Rolls-Royce Merlin-powered entry.

Fults died of a broken neck when he encountered a wake and was flipped out of the boat. He had been wearing a car racing helmet, which was permitted–but not recommended–for boat racing.

Built by Les Staudacher, the BUZZARD had won the 1970 Tri-Cities Atomic Cup and had the distinction of turning the fastest heat of the 1970 season at Seattle (108.433) with Fults at the wheel.

PAY ‘n PAK’S ‘LIL BUZZARD never raced again after 1970. It sat in storage for several years and eventually became an ATLAS VAN LINES display hull.

For 1971, Heerensperger hired Billy Schumacher as driver and promoted Jim Lucero to crew chief. During the off-season of 1970-71, Lucero changed the PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK from a cabover to a conventional configuration with the cockpit situated behind–rather than in front of–the engine well. Lucero replaced the twin Chryslers with a single Rolls-Royce Merlin. The boat was wider, flatter, and less box-shaped than most Unlimiteds of that era.

The Merlin-powered PAK performed unevenly in the first half of 1971. But there were those who believed that if PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK ever had the “bugs” ironed out of her, she would revolutionize the sport, and render obsolete all of the top contenders of the previous twenty years. This ultimately proved to be the case.

Schumacher powered the PAK to victory in the last three races of the season at Seattle, Eugene, and Dallas and set a world lap speed record of 121.076 in qualification at Seattle. The boat that had disappointed so badly the year before as an automotive-powered cabover, now ruled the Unlimited roost.

Dave Heerensperger now had seven race wins as an owner. His team’s recent difficulties seemed a thing of the past. PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK seemed poised for a National Championship bid in 1972. But things didn’t work out that way.

Joe Schoenith’s ATLAS VAN LINES team, after an uneven 1971, had its act together in 1972 and driver Bill Muncey was really on a roll. Schumacher and PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK ran a frustrating second to Muncey at each of the first three races of the season at Miami, Owensboro, and Detroit.

Schumacher and Lucero were at odds on how to set up the boat. After being decisively defeated in every race by ATLAS VAN LINES, Schumacher left the PAY ‘n PAK team the weekend after Detroit at Madison, Indiana.

Where Schumacher and Lucero were concerned, it was a case of an irresistible force against an unmovable object.

On a race team, there can be only one leader. Everyone must pull in the same direction. A team must be unified or there is chaos.

Former champion Bill Sterett, Sr., came out of retirement to pilot the PAK at Madison. He failed to start in Heat One but ran the fastest heat of the race in Heat Two. (Heat Three was cancelled due to inclement weather conditions.)

PayNPak in DC – Bill Sterett Jr

Billy Sterett, Jr., drove the last three races of the 1972 season. He scored a sensational victory over ATLAS VAN LINES in the President’s Cup and, in so doing, handed Bill Muncey his only defeat of the year. After a frustrating series of early-season setbacks, PRIDE OF PAY n PAK appeared to be back on track and highly favored for the Atomic Cup and Seafair Trophy races.

Sterett, Jr., and the PAK were indeed an awesome sight to behold during qualification at the Pacific Northwest regattas. They qualified fastest at both events. And, at Seattle, the team achieved owner Heerensperger’s goal of a lap of 125 miles per hour with a clocking of 125.878 on a 3-mile course.

Race day was a different story. At the Tri-Cities, after winning the first two heats, the Rolls engine conked out at the start of the finale. At Seattle, PRIDE OF PAY ‘n PAK again experienced mechanical difficulty and failed to complete even a single lap. In Heerensperger’s words, “When we’re hot, we’re hot. Today, we’re not.”

At this point, Dave decided to accept an offer from his good friend Bernie Little, the MISS BUDWEISER owner, and sold his record-holder to the Anheuser-Busch team. The day after the Seafair race, Heerensperger met with designer Ron Jones to plan a new boat for 1973, the “Winged Wonder,” which would prove to be one of the most significant boats in hydroplane history.

After 1972, the words PRIDE OF were dropped from the Heerensperger team’s official name. For the rest of Dave’s racing career, all of his boats would be known as simply PAY ‘n PAK. The 1973 “Winged Wonder” was the first hydroplane of any shape or size to be built of aluminum honeycomb, rather than marine plywood.

According to Jones, “I had originally thought that I would use a honeycomb bottom. But after talking with the people from the Hexcel Company, I was very impressed and decided to use it everywhere in the boat that I possibly could for a weight saving of about a thousand pounds.”

Pay N Pak

In planning the new PAY ‘n PAK, Jones wanted very much to build a cabover. But Heerensperger insisted on a rear-cockpit hull and won out. Ron nevertheless utilized many of the cabover hull characteristics while still seating the driver behind the engine.

“But I did insist on the use of a horizontal stabilizer. Heerensperger agreed because it would give him a lot of publicity. And it did. Perhaps, by today’s standards, the stabilizer was not everything it could have been. It was, however, a good running start on the widespread use of the concept. And in all fairness to Jim Lucero, he certainly added to the boat’s ultimate performance by preparing excellent engines, good gearbox/propeller combinations, and probably some fine-tuning on the sponsons.”

The “Winged Wonder” PAY ‘n PAK set a Gold Cup qualification record for two laps in 1973 at 124.309 on the 2.5-mile Columbia River course. This translated to approximately 129 miles per hour on a 3-mile course.

The 1973 season was the first in which the majority of races were won by Ron Jones-designed hulls. The new PAY ‘n PAK and its predecessor (now the MISS BUDWEISER) won four races apiece on the nine-race circuit.

At Seattle in 1973, the PAY ‘n PAK with Mickey Remund and the MISS BUDWEISER with Dean Chenoweth became the first two teams to average over 120 miles per hour in a heat of competition. And they did this in a driving rain! MISS BUDWEISER averaged 122.504 for the 15 miles; PAY ‘n PAK did 120.697. A local newspaper labeled the PAK and the BUD as “the champion fogcutters of the world.”

Pay N Pak and Bud

Although not significantly faster on the straightaway than the traditional post-1950 Ted Jones-style hulls, the Ron Jones-designed PAY ‘n PAK and MISS BUDWEISER could out-corner anything on the water. Both boats were helped considerably by the inclusion of an outboard skid fin. The skid fins helped greatly in holding the boats in their lanes through the turns.

In spite of being three years older and a thousand pounds heavier than PAY ‘n PAK, MISS BUDWEISER was able to achieve parity with the PAK. This was due to driver Chenoweth consistently securing the inside lane in heat confrontations between the two entries. PAY ‘n PAK ended up with the first of the team’s three consecutive National High Point Championships in 1973. The only major disappointment was at the Tri-Cities Gold Cup.

Pilot Remund appeared to have things well in hand. He won his three preliminary heats and had a clear lead in the finale. Then, on lap-two, the PAK lost a blade on its propeller. The boat bounced crazily a couple of times and settled to a stop. MISS BUDWEISER went on to claim the victory. This was a most unfortunate turn of events for Remund who had posted a Gold Cup competition lap record of 119.691 miles per hour on the first lap of the Final Heat on a 2.5-mile course.

The 1973, ‘74, and ‘75 seasons are fondly remembered as “The PAK/BUD Era” of Unlimited racing. The many side-by-side battles by those two awesome machines are unforgettable. Their owners, too, were larger than life. Dave Heerensperger and Bernie Little gave no quarter and asked for none. To them, second-place was an insult.

And yet, as competitive as their teams were out on the race course, the two men were close personal friends. In 1974, when Dave married his wife Jill, Bernie was Best Man at their wedding.

PAY ‘n PAK and MISS BUDWEISER picked up in 1974 where they had left off in 1973–but this time with different drivers. George Henley now occupied the PAK’s cockpit; Howie Benns handled the BUD. (Chenoweth did briefly return to the BUDWEISER team in late season after Benns suffered a broken leg in a motorcycle accident.) The PAK won seven races and the BUD won four.

The most memorable PAK/BUD match-up of 1974 would have to be the 1974 Seattle Gold Cup at Sand Point. Delays, controversy, and rough water marred the running of the race but PAY ‘n PAK finally prevailed and Dave Heerensperger was able to take his first Gold Cup home–but only after a titanic struggle.

Henley and Benns battled head to head all day long in some of the finest racing ever witnessed in the Unlimited Class. PAY ‘n PAK won all four heats with MISS BUDWEISER always within striking distance. The BUD had the lead in Heat 1-C but spewed oil briefly and was overtaken by PAY ‘n PAK. Heat 1-C was the fastest of the day with Henley averaging 112.056 miles per hour and Benns 109.845. No one else averaged over 100 all day long because of the rough water.

George Henley made it two Gold Cups in a row for Heerensperger at the Tri-Cities in 1975. The “Winged Wonder” won her three preliminary heats and then cruised to an easy third in the finale behind Tom D’Eath in MISS U.S. and Milner Irvin in LINCOLN THRIFT.

In the space of three years, the low-profile/wide-afterplane Ron Jones-style hull had become the dominant design in Unlimited racing. (Ted Jones, Ron’s father, had likewise revolutionized the sport in the 1950s, starting with SLO-MO-SHUN IV.)

The PAY ‘n PAK’s road to victory in 1975 was not an easy one. After a stellar 1974 campaign, George Henley retired as driver and Jim Lucero rebuilt the boat. In spring testing, PAY ‘n PAK was definitely faster on the straightaways but was skittish in the turns.

New driver Jim McCormick (on the rebound from a serious injury accident in 1974 with RED MAN) had great difficulty in cornering the PAK and was the subject of considerable criticism. McCormick retired from racing after a third-place finish in the 1975 President’s Cup.

Henley was coaxed out of retirement and returned to the PAY ‘n PAK cockpit at the third race of the season in Owensboro, Kentucky. Lo and behold, George had the same problem with the PAK that Jim had experienced. On the first lap of the first heat at Owensboro, PAY ‘n PAK swapped ends, caved in a sponson, and had to be withdrawn. All of a sudden, the Jim McCormick detractors became the George Henley apologists.

PAY ‘n PAK continued to perform badly at the next race in Detroit. Finally, Lucero restored the boat to its 1974 configuration. Only then was the PAK its old competitive self again. Henley and PAY ‘n PAK picked up where they had left off the year before with victories at Madison, Indiana, and Dayton, Ohio. After winning at the Tri-Cities, the team went on to take first-place in Seattle and San Diego en route to a third consecutive National High Point Championship.

Earlier in the season, the Billy Schumacher-chauffeured WEISFIELD’S had seemed a shoo-in for the national title. They had scored convincing victories at Miami and Owensboro and finished second at Washington, D.C. But once PAY ‘n PAK was back on track, the chances for a WEISFIELD’S championship promptly vanished.

The MISS BUDWEISER team had an uneven 1975 campaign. They won two races (at Washington, D.C., and Phoenix, Arizona) with Mickey Remund driving, but in general lacked the consistency that marked the 1973 and 1974 seasons.

After two dozen race victories and having re-written the speed record book from coast to coast, Heerensperger decided to rest on his laurels for a while. “We’ve accomplished everything we set out to do and more.”

In January of 1976, he accepted an offer from Bill Muncey’s ATLAS VAN LINES team and sold the entire PAY ‘n PAK equipment inventory for a figure in the six digits. Inactive as an owner between 1976 and 1979, Dave nevertheless stayed close to the sport that he loved. He sponsored the boat that he had most recently owned–the ”Winged Wonder”–at two 1977 races. He also sponsored the 225 Class WHITE LIGHTNING, owned and driven by Steve Reynolds, as PAY ‘n PAK.

Always on the lookout for new ideas, Heerensperger began serious speculation into the possibility of turbine power in an Unlimited hydroplane. Between 1980 and 1982, he campaigned just such a craft. Jim Lucero designed the hull. The highly regarded Dixon Smith, who happened to be Heerensperger’s personal pilot, developed the turbine engine concept.

Turbine Pay N Pak

The turbine PAY ‘n PAK was the first turbine-powered Unlimited since Pam Clapp’s U-95 in 1974. Unlike the U-95, which used a pair of T-53 engines, PAY ‘n PAK used a single Lycoming T-55 power plant, thereby establishing a precedent for turbine-powered Unlimiteds of the future.

The new boat’s first appearance (at the 1980 Tri-Cities Columbia Cup) proved disastrous. Rookie driver John Walters flipped the boat in trials on the Columbia River and delayed the team’s competition debut until the following year. Walters steered the turbine PAY ‘n PAK to some high finishes in 1981, which included a second-place performance in the Champion Spark Plug Regatta at Miami and a second in the Gold Cup at Seattle.

During the Final Heat of the Gold Cup, Walters gave the winner Dean Chenoweth in the MISS BUDWEISER everything he could handle. MISS BUDWEISER averaged 123.814 to PAY ‘n PAK’s 122.223.

The PAK finally achieved victory in 1982 at “Thunder In The Park” at Romulus, New York. In the long history of Unlimited hydroplane competition, this was a famous first–the first victory by a non-internal combustion-powered craft.

The turbine was the power source of today. In contrast, the Allison, the Rolls-Royce Merlin, and the Rolls-Royce Griffon had ceased production almost forty years earlier.

Her triumph at Romulus not withstanding, PAY ‘n PAK did not have much of an opportunity to build upon this accomplishment. The boat damaged its right sponson in Heat 1-B at the Gold Cup in Detroit and had to withdraw. A few weeks later, Walters was badly hurt and the boat was extensively damaged in an accident at the Emerald Cup on Lake Washington.

Pay N Pak flips in Seattle

Moments after the start of Heat 1-B at Seattle, George Johnson, driving EXECUTONE, experienced rudder failure. The boat dug in its right sponson and veered to the left and crashed into the right side of Tom D’Eath and THE SQUIRE SHOP. The impact sent EXECUTONE back to the right and into the path of a late-starting PAY ‘n PAK. The PAK ran right over EXECUTONE and flipped. EXECUTONE sank almost immediately. THE SQUIRE SHOP managed to limp back to the pits under its own power, while PAY ‘n PAK had to be towed back to the dock.

Johnson and D’Eath were unhurt. But Walters was critically injured with several broken bones and a collapsed lung. John recovered and continued in the sport for many years as a shore mechanic. But he never drove in competition again.

After the accident to his boat and the injury to his driver, Dave Heerensperger announced his retirement from Unlimited racing and sold his team to Steve Woomer. Heerensperger had first joined the sport in 1963 as the sponsor of MISS EAGLE ELECTRIC. “Dynamite Dave” had left before. But this time it was for good.

As in the case of the U-95 eight years earlier, the PAY ‘n PAK team’s innovative turbine concept passed into history, but not for long. In the not too distant future, the Lycoming turbine engine would return and revolutionize the sport.

Thanks to Bill Osborne & The Hydroplane and Raceboat Museum for photos